A Monumental Mystery

The Story of a Small Town’s Lawn-Cannon and Public Memory

August 1, 2023

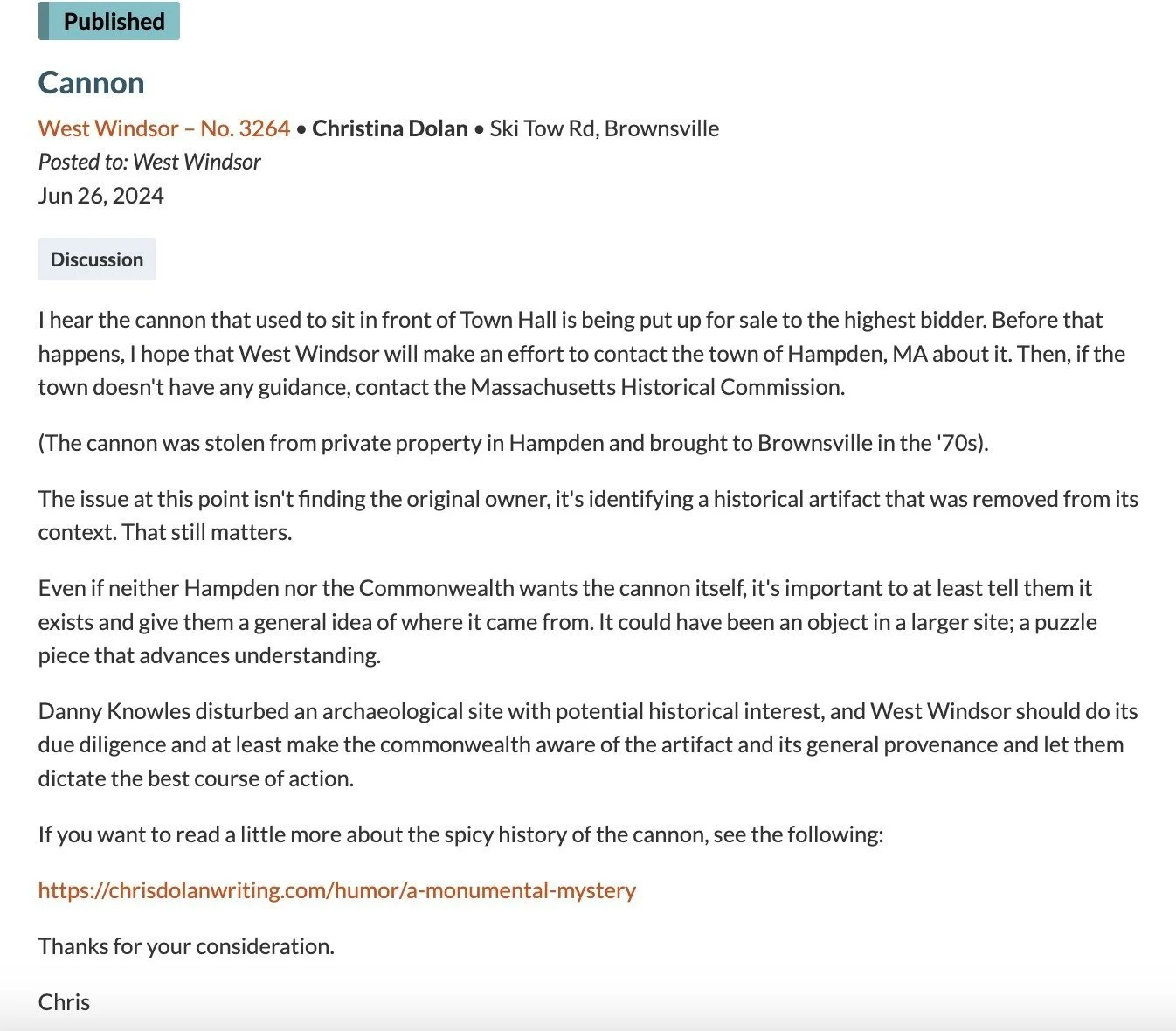

The “4th of July” Cannon in its former home outside the West Windsor, Vermont, municipal building.

Last summer, a set of rotted and flaking wooden carriage wheels exposed intriguing questions about West Windsor’s town cannon.

At the May 8, 2023, Selectboard meeting, Chair Matt Kantola made a motion to remove the cannon from the Town Hall lawn, where it has sat for nearly two decades. “I don’t like the warlike tone of it … it doesn’t seem very welcoming,” he said, noting also that its deteriorating condition has made it an “eyesore.”

One resident disagreed with the Chair’s aesthetic assessment, saying “I don't think it's an eyesore. I find it charming, and getting rid of it without discussion is, I think, a mistake.” Another offered that considering Vermont’s history during the Revolutionary era, the cannon has value as a symbol of the state’s self-reliance. (And at least one new resident has wondered why the town cannon pointed directly at the neighbor’s house.)

A brief discussion ensued about whether the cannon has any historical value, but little seemed known about its origins other than that longtime Brownsville resident Danny Knowles had kept it in his yard and fired it off during Brownsville’s Fourth of July celebrations during the 1990s. After his death in late 2003, it was acquired by the town and displayed beneath the flagpole, accompanied by a stone marker that reads: “WW 4th of July Cannon, 2004, Honoring Danny Knowles”

The motion to remove the cannon was tabled until more research could be done. But then at its May 22 meeting, the Selectboard voted unanimously to remove it to the highway garage, although no further information about it seemed to have been gathered.

What does seem clear is that the cannon was placed in front of the town hall simply to honor Mr. Knowles for providing residents with happy memories, rather than for any larger historical purpose. In other words, there is no evidence that the cannon itself played any role in the fight for American independence. For West Windsor, there was simply a shared community value in honoring Mr. Knowles for his contributions to Independence Day celebrations.

From Private Object to Public Monument

The May 8 discussion, though, exposed the wide range of ways that we understand and assign meaning to historical artifacts. One person’s distasteful war machine is another’s endearing artifact or someone else’s icon of Vermont identity. That variety of views betrays a fact that Americans often find uncomfortable: that despite a shared history, choices are constantly being made by and for us about what aspects of our history are worth remembering, and how they should be remembered. The phrase “there are two sides to every story” gets it wrong by a long shot. There are about as many sides to a story as there are people who know the story. And not knowing a story is its own perspective.

So what happens when we learn more about the origin and context of a familiar object that we’ve already assigned meaning to? If we discover that our cannon has a past that we may not necessarily want to celebrate, does that dampen the fond memories of its role in Independence Day celebrations? Sully its visual charm?

New Discoveries about an Old Friend

According to research by Ruth Rhynas Brown and Jack Dugdale and provided to the West Windsor Historical Society, the Town Hall cannon is probably of a relatively common type carried on merchant vessels (as opposed to warships) and may have been cast in Sweden sometime in the 17th or early 18th centuries. It was likely purchased for use on a Dutch ship, though of course it could have been captured by or sold to almost anyone. Certainly the Dutch would have been actively trading along the Connecticut River in the 17th century, so finding the cannon in southwestern Massachusetts wouldn’t have presented any Area-51-worthy anomalies. Unfortunately, the deteriorating condition of the barrel makes it challenging to discern details that would identify it more closely.

According to Brown and Dugdale, “there are a hundred ways that cannon could have made it to the US.” And we will probably never know exactly how it ended up in a field in southwestern Massachusetts, where Knowles found it in the mid-1970s.

The Brownsville Era

In a 2003 interview, Danny Knowles said that he had been working as a policeman and chasing a suspect through the woods when he tripped over the cannon. The barrel was buried vertically, with its open end down. Mr. Knowles later returned to the spot with a tow truck and without the owner's knowledge or permission spent six hours digging it up before taking it home. He later brought it to Brownsville and displayed it in his yard. He seemed unconcerned about the property owner’s rights to the cannon, saying “they didn’t even know it was there.”

Toward the end of his life, Knowles began trying to sell the cannon, and in 2003 the town of Lakeville, MA agreed to buy it from him for $6,000. That purchase never transpired, though, and it’s not entirely clear why. Mr. Knowles died in December of 2003, just a few months after the purchase agreement, which may have scuppered the deal. But also, Lakeville's Selectboard evidently had concerns about the liability involved in purchasing an item with such a murky provenance.

In retrospect, the Town of West Windsor might have asked a few more questions about the cannon before placing it in a public space, if only to be more aware of and intentional about its public message.

Is it as pleasing and innocuous, for example, when we learn that it was unapologetically stolen by a law enforcement officer? That it may have protected ships carrying slaves or engaged in piracy? At best, it seems to have guarded vessels carrying lucrative commodities. If it was used in any more noble cause, such as the Revolutionary War, we have no evidence. Indeed, Mr. Knowles made it even more difficult for us to know whether the cannon had a past worth honoring when he made off with it without marking the site or alerting any local historical entities to his find.

To discover and acknowledge a more complex past for a familiar object doesn’t “change” history. But it often changes the way we think about public symbols, what they represent, and to whom. In the case of the mysterious cannon, the new awareness of its past asks us to do the heavy lifting of considering many meanings simultaneously.

History itself is an intellectual “jaws of life” tool. If we reckon with it in good faith, it inexorably pries open our worldviews, broadening and deepening our understanding of the past. The result is a more meaningful and richly textured sense of not only our history, but ourselves.

The cannon should be returned, either to its owner or to the town of Hampden, MA, where state and local historical commissions can evaluate not just the cannon, but the site where it was located. When Mr. Knowles quietly absconded with it, he deprived Hampden of not just an artifact, but an archaeological site that may have served as an important puzzle piece in its local and regional history.

The “4th of July cannon” will continue to live in the memory of many West Windsor residents, but it doesn’t rightfully belong to us. Its twenty-year stay in central Vermont is just one era in its long and mysterious provenance.

(Please note that this piece was not produced or reviewed by the West Windsor Historical Society. The Society was simply kind enough to make Brown and Dugdale's research available. The reflections expressed here are solely those of the writer).

References

Barnes, Jennette. “Town agrees to buy cannon,” The Standard Times (New Bedford, MA), October 23, 2003.

Cannon Research: Ruth Rhynas Brown (cannon identification and history of the type) and Jack Dugdale (recent history of the cannon). Provided courtesy of the West Windsor Historical Society.